Explaining The Neglect of Doug Engelbart’s Vision

The Economic Irrelevance of Human Intelligence Augmentation

Key Points:

- Engelbart's vision of augmenting human intellect was not widely adopted because most people prefer easy-to-use systems rather than investing in learning complex tasks.

- In professional computing, the focus has shifted towards making machines smarter and humans dumber to optimize total system performance and reduce costs.

- The trend of automation has led to the deskilling of human operators in both manufacturing and information sectors.

- The neglect of Engelbart's vision in favor of artificial intelligence has resulted in a reliance on semi-automatic systems where humans are needed for tasks that cannot be fully automated.

- The downside of neglecting Engelbart's vision is that skilled human operators are still necessary to monitor and handle unexpected scenarios when automated systems fail.

- The challenge lies in balancing the reliance on machines for most tasks while ensuring that humans maintain enough skill to intervene when needed during emergencies or system failures.

Doug Engelbart’s work was driven by his vision of “augmenting the human intellect”:

By “augmenting human intellect” we mean increasing the capability of a man to approach a complex problem situation, to gain comprehension to suit his particular needs, and to derive solutions to problems.

Alan Kay summarised the most common argument as to why Engelbart’s vision never came to fruition 1:

Engelbart, for better or for worse, was trying to make a violin…most people don’t want to learn the violin.

This explanation makes sense within the market for mass computing. Engelbart was dismissive about the need for computing systems to be easy-to-use. And ease-of-use is everything in the mass market. Most people do not want to improve their skills at executing a task. They want to minimise the skill required to execute a task. The average photographer would rather buy an easy-to-use camera than teach himself how to use a professional camera. And there’s nothing wrong with this trend.

But why would this argument hold for professional computing? Surely a professional barista would be incentivised to become an expert even if it meant having to master a difficult skill and operate a complex coffee machine? Engelbart’s dismissal of the need for computing systems to be easy-to-use was not irrational. As Stanislav Datskovskiy argues, Engelbart’s primary concern was that the computing system should reward learning. And Engelbart knew that systems that were easy to use the first time around did not reward learning in the long run. There is no meaningful way in which anyone can be an expert user of most easy-to-use mass computing systems. And surely professional users need to be experts within their domain?

The somewhat surprising answer is: No, they do not. From an economic perspective, it is not worthwhile to maximise the skill of the human user of the system. What matters and needs to be optimised is total system performance. In the era of the ‘control revolution’, optimising total system performance involves making the machine smarter and the human operator dumber. Choosing to make your computing systems smarter and your employees dumber also helps keep costs down. Low-skilled employees are a lot easier to replace than highly skilled employees.

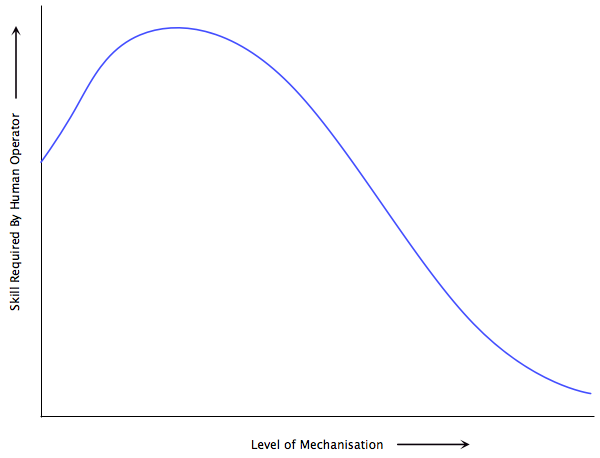

The increasing automation of the manufacturing sector has led to the progressive deskilling of the human workforce. For example, below is a simplified version of the empirical relationship between mechanisation and human skill that James Bright documented in 1958 (via Harry Braverman’s ‘Labor and Monopoly Capital’). However, although human performance has suffered, total system performance has improved dramatically and the cost of running the modern automated system is much lower than the preceding artisanal system.

AUTOMATION AND DESKILLING OF THE HUMAN OPERATOR

Since the advent of the assembly line, the skill level required by manufacturing workers has reduced. And in the era of increasingly autonomous algorithmic systems, the same is true of “information workers”. For example, since my time working within the derivatives trading businesses of investment banks, banks have made a significant effort to reduce the amount of skill and know-how required to price and trade financial derivatives. Trading systems have been progressively modified so that as much knowledge as possible is embedded within the software.

Engelbart’s vision runs counter to the overwhelming trend of the modern era. Moreover, as Thierry Bardini argues in his fascinating book, Engelbart’s vision was also neglected within his own field which was much more focused on ‘artificial intelligence’ rather than ‘intelligence augmentation’. The best description of the ‘artificial intelligence’ program that eventually won the day was given by J.C.R. Licklider in his remarkably prescient paper ‘Man-Computer Symbiosis’ (emphasis mine):

As a concept, man-computer symbiosis is different in an important way from what North has called “mechanically extended man.” In the man-machine systems of the past, the human operator supplied the initiative, the direction, the integration, and the criterion. The mechanical parts of the systems were mere extensions, first of the human arm, then of the human eye….

In one sense of course, any man-made system is intended to help man….If we focus upon the human operator within the system, however, we see that, in some areas of technology, a fantastic change has taken place during the last few years. “Mechanical extension” has given way to replacement of men, to automation, and the men who remain are there more to help than to be helped. In some instances, particularly in large computer-centered information and control systems, the human operators are responsible mainly for functions that it proved infeasible to automate…They are “semi-automatic” systems, systems that started out to be fully automatic but fell short of the goal.

Licklider also correctly predicted that the interim period before full automation would be long and that for the foreseeable future, man and computer would have to work together in “intimate association”. And herein lies the downside of the neglect of Engelbart’s program. Although computers do most tasks, we still need skilled humans to monitor them and take care of unusual scenarios which cannot be fully automated. And humans are uniquely unsuited to a role where they exercise minimal discretion and skill most of the time but nevertheless need to display heroic prowess when things go awry. As I noted in an earlier essay, “the ability of the automated system to deal with most scenarios on ‘auto-pilot’ results in a deskilled human operator whose skill level never rises above that of a novice and who is ill-equipped to cope with the rare but inevitable instances when the system fails”.

In other words, ‘people make poor monitors for computers’. I have illustrated this principle in the context of airplane pilots and derivatives traders but Atul Varma finds an equally relevant example in the ‘near fully-automated’ coffee machine which is “comparatively easy to use, and makes fine drinks at the push of a button—until something goes wrong in the opaque innards of the machine”. Thierry Bardini quips that arguments against Engelbart’s vision always boiled down to the same objection - let the machine do the work! But in a world where machines do most of the work, how do humans become skilled enough so that they can take over during the inevitable emergency when the machine breaks down?